Can the Rover Scout Vigil Change the Community Which Values It?

An analysis of the Rover Vigil as ritual

I. The Scout Movement

Globally, the Scout Movement is defined as "a voluntary, non-political, educational movement for young people, open to all without distinction of origin, race, or creed, in accordance with the purpose, principles and method conceived by the Founder" (WOSM 1992:2). That is to say, individuals freely choose to join this brotherhood in order to develop oneself through the acquisition of knowledge and skills. This is not a movement designed for adults, but rather uses the experiences of adults in assisting the youth to develop themselves.

A. Purpose of the Scout Movement

The sole purpose behind this global movement is "to contribute to the development of young people in achieving their full physical, intellectual, social, and spiritual potentials as individuals, as responsible citizens and as members of their local, national and international communities" (WOSM 1992:4). It is through this statement that one can see the emphasis on the educational or developmental character of the movement, promoting "responsible citizenship" (WOSM 1992:2). Therefore, through creating these "ideal citizens," the Scouting Movement worldwide facilitates an environment which the identities of these "ideal citizens" are created and fostered within the Scouting world view.

B. The Principles of the Scout Movement

The purpose of the Scout Movement is manifested through its principles. Among these many principles, the most important of these are the "Duty to self" and the "Duty to others." The World Organization of the Scout Movement (WOSM) defines "Duty to others" as a "loyalty to one's own country in harmony with the promotion of local, national and international peace, understanding and cooperation" and that "participation in the development of society, with recognition and respect for the dignity of one's fellow-man and for the integrity of the natural world" (WOSM 1992:5). It is this belief which attaches importance to the concepts of "brotherhood" across nationality. The service which Scouts provide should be a "contribution to the development of society" (WOSM 1992:5). It is for this reason that rituals, such as the Vigil within Rover Scouts has the potential to change the community which values it.

The "Duty to others" is accomplished, at least in part, through the "Duty to self." One's "Duty to self" is that each Scout is responsible for the development of themselves (WOSM 1992:6). It is in this forum that the educational purpose of the movement arises, "whose aim is to assist the young person in the full development of his potential — a process which has been called the 'unfolding' of the personality" (WOSM 1992:6). It is precisely this "unfolding" of a youth's personality which not only plays a role in the creation of the youth's individual identity, but also has the potential to change the community within which that youth is a member.

II. The Canadian Case

Within Canada, a secular youth organization, Scouts Canada, participates in the creation of individual identities through a series of youth classifications, or "sections." The youngest section within the Scouting Movement in Canada is that of "Beavers", for children from age five (Scouts Canada 1996:17). As a youth gets older, it will move progressively through the other sections. New members can join at any time within this process. The final youth section, the Rover Scouts, is designed for young adults, aged eighteen to twenty-six. These Rover Scouts create their own programs (Scouts Canada 1974:23), and perform their own rituals in order to help develop these young adults into productive members of the community on the local, national, and international level.

A. The Rover Scout Community

Before proceeding with an anthropological investigation into the ritual of the Vigil, it is necessary to introduce the Rover Scouts as a community. The Rover section is one of three sections initially designed by the founder of Scouting, Lord Robert Baden-Powell of Gilwell in the early twentieth century. In order for others to understand his vision for this section, Baden-Powell wrote a book entitled Rovering to Success in 1922. In Canada, the Rovering section was envisioned and designed to help its members to make the most of the activities of the open air and to fit them, bodily, mentally, and spiritually to render effective service to the community. Its scheme of activities and training, developed from the experience of the past, adapted and expanded to meet changing needs and circumstances, will achieve this and, additionally, will lead the young man into, not away from, the adult community. Rover Scouting endeavours to send into that adult community men who will cork for the common good, men trained to think for themselves, men of sound judgement; men who accept readily the highest ideals of chivalry, clean living, tolerance and helpfulness; men with the courage of their opinions, opinions based upon knowledge and experience. (Scouts Canada n.d.a:5-6)

That is to say, in order to develop the physical, emotional, and spiritual character of the nation's youth, the Rover Scout section would undertake activities and training in order for the youth of today to meet the needs of an ever-changing world. This is accomplished by fostering a safe environment in which the youth can learn to think for themselves, have sound judgement, and perform service for the community at large. The first blueprint to developing these productive young adults was, in fact, Rovering to Success (Baden-Powell 1922).

III. Blueprint of the Community: Rovering to Success

Rovering to Success was designed to be a handbook for both the Rover Scouts themselves, and the leaders who guided the youth's development. In it, Baden-Powell outlines that the only true success in life is "happiness" (ibid:15). However, in order to achieve this "happiness" a Rover Scout must successfully navigate the five stumbling blocks, or "Rocks" which can prevent this "happiness." Therefore, Baden-Powell outlines as well as the "Rocks" the means by which to avoid them.

The chapter entitled "Horses" deals primarily with the difference between "sport" and "false sport" (ibid:30). Baden-Powell outlines how to avoid "false sport" by discussing such things as "cleansport," "hobbies," "livings," "responsibilities," "thriftiness," and "service" which warning against gambling (ibid:30). That is to say, the degeneration of youth can occur as a result of cheating and gambling, and it is through hobbies, earning respectable livings, having responsibilities, and performing service that the youth can avoid such degeneration which would not benefit the community.

The "Rock" which must be avoided in the "Wine" chapter is that of overindulgence and temptation (ibid:66). This overindulgence can manifest itself as "over-eating," "over-sleeping," and "over-working" (ibid:66). This "Rock" can be avoided, according to Baden-Powell, through the development of "self-command," namely through self-control, self-respect, loyalty, and strength of character (ibid:66). Therefore, by respecting your body and yourself, you are better able to perform service for your community.

In the "Women"1 chapter, Baden-Powell describes sexual instincts and their risks (ibid:100). In this section, the youth learns about changes to their bodies and hormones, and the potential risks of sexual encounters. In order to avoid this "Rock," Baden-Powell outlines the characteristics that men should possess and discusses what the institution of marriage is (ibid:100). That is to say, manliness is characterized by chivalry, good parenting, service and hygiene. The section on marriage outlines not only how to choose the "right girl" but also the responsibilities of the husband, such as bringing an income into the home, how to deal with debts, and the joy of children.

It is in the chapter entitled "Cuckoos and Humbugs" that education is emphasized the most. Baden-Powell outlines for the Rover Scout how books should be read, and that both travel and self-expression such as art are all methods for self-education (ibid:134). The "Rock" to be avoided in this case is ignorance. Through this self-education, the youth can draw on both experiences and knowledge to come to conclusions. In this way, the Rover Scout is then better prepared for civil service since his education, according to Baden-Powell, should centre around public work, government, and international relations, taking every opportunity to be "good" citizens of their local, national, and international communities (ibid:134).

In the case of "Irreligion," irreligion does not being of a "wrong" religion, but rather that each individual, regardless of religious choice, should be in some way spiritual. Therefore, the "Rock" being avoided here is Atheism (ibid:174). For Baden-Powell, the outdoors is the safeguard against Atheism because it is through nature that an understanding of the divine can develop. This would also, therefore, instill humility and reverence in the Rover (ibid:174). By coming to understand nature, the Rover Scout also comes to understand his body, his mind, and the world around him (ibid:174).

The preceding chapters are guidelines for any young adult to find happiness. Therefore, the final chapter of Rovering to Success presents how this framework should operate within the Scouting community. Baden-Powell outlines the objectives of the Rover Movement, namely, creating good citizens for the nation (ibid:204). The methodology employed to facilitate this development were the concepts of "service," "brotherhood," and the outdoors (ibid:204). Therefore, Baden-Powell outlined the organization of the Rover Scouts such as "how to start," "training," "uniform," "service," "recreation" (ibid:204). Therefore, through reading this book, the Rover Scout comes to an understanding of not only what the community value in its members, but also how to develop themselves in order for their own identity to match that of the "ideal."

IV. Methodology

A. Rites of Passage

In his book, The Rites of Passage, Arnold van Gennep (1960) outlines his theory of ritual. He suggests that patterns of behaviour accompany any ritual in which a passage occurs "from one situation to another or from one cosmic or social world to another" (van Gennep 1996:530). This ritualistic process was, by van Gennep, separated into three stages, the pre-liminal or separation rites, the liminal or transitional rites, and the post-liminal or reincorporation rites. However, all ceremonies have both their individual purposes and their individual results. Therefore, it is the essence of a ritual "to enable the individual to pass from one defined position to another which is equally well defined" (van Gennep 1960:3).

B. Liminality

Victor Turner, taking up van Gennep's work, elaborated on the liminality of van Gennep's transitional rites. Turner felt that this time was "necessarily ambiguous" and that these liminal personae or "threshold people" "elude or slip through the network of classification that normally locates states and positions in cultural space" (Turner 1996:512). According to Turner, within this temporal space of liminality specific symbols are employed which "ritualise social and cultural transformations" (Turner 1996:512). For example, the Rover Scout community use symbols from the stories of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table throughout their rituals. However, this theme of knighthood is emphasized the most during the knighting ceremony which initiates the neophytes into the society as full, adult members of the community.

V. The Vigil

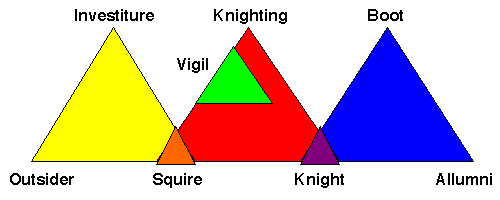

However, as van Gennep points out (1960:11), "where the transitional period is sufficiently elaborated to constitute an independent state, the arrangement is reduplicated." When the rite of passage is envisioned as a triangle there are three major rites of passage in Rover Scouting, as seen in Figure 1 of the "investiture," the "knighting," and the "boot," which can be envisioned as the birth, puberty, and death rites of the community respectively. However, it should be noted that even within the major rites of passage within Rover Scouting, there are also smaller ones such as the Vigil.

Often, as part of van Gennep's separation rites, purifications are undertaken which, in effect, separate those involved from the mundane world (van Gennep 1996:532). In terms of the major rite of passage within Rover Scouting, the Knighting Ceremony, a purification ritual is undertaken by the neophyte in preparation for this ritual. This purification ritual is called the "Vigil." Peter Kirchmeir, a Rover Scout Adviser from Edmonton, Alberta, defines a vigil as "part of the knighthood theme. A Squire is required in some crews, to stand a vigil before being invested as a Rover" (Kirchmeier n.d.: "vigil"). However, this definition does not enlighten the reader to the creative potential of this ritual.

A. Origin of the Vigil

It is precisely the theme of knighthood which is prevalent throughout all of the Rover Scout rituals which emphasize the terminology of the ritual. Before becoming a knight, traditionally the Squire, or Knight in training, spends the night before his knighting in the abbey reflecting on his past actions and reflecting on new responsibilities if he does in fact go through with the knighting ceremony. It is precisely this process which is undertaken by Squires within Rover Scouting. The Squire is asked to "think carefully before taking this important step and should not commit themselves to serious promises or principles until they are resolved to do their best to keep them" (Morland 2000). The sentiment of Liam Morland from Ontario, which is common to most Knighted Rovers, is that "The Vigil should only be read by Knighted Rovers and those Squires who have completed all other requirements for Knighthood. The Vigil is more effective and special if it is kept mostly secret." (Morland 2000) It is for this reason that I will not include the Vigil questions in this paper. It is this secrecy which allows for the serious contemplation of the commitment the Squire is about to undertake.

B. The Creative Potential of the Vigil

A pamphlet was drawn up outlining not only the retrospective questions the Squire is to reflect upon, but also a description of the Chief Scout's, Baden-Powell's, intent for the vigil. According to the pamphlet, the vigil of a Rover Scout occurs at the end of a probationary period, or Squireship. The purpose of the vigil is for the young man, before becoming a Rover Scout, and with the aid of the questions drawn up by the Chief Scout, to quietly think to themselves about what he is doing with his life, and determine whether he is prepared to be invested as a Rover Scout renewing or making his Scout Promise from the man's point of view" (Scouts Canada n.d.b). The Squire should be resolved to keep his promise which he is about to make. Therefore, through the vigil a period of self-examination occurs in which "the young man reviews the past, thinks of future possibilities dimly seen, and dedicates himself in silence to the Service of God, and his fellow men" (Scouts Canada n.d.b).

C. The Vigil as part of Identity

The vigil is an integral ritual to the larger whole of the knighting ceremony. "Without this the Rover Scout Investiture [knighting] cannot be what it is meant to be — an inward change of attitude to life in the world" (Scouts Canada n.d.b). That is to say, during the knighting ceremony the Squire is ritually and symbolically dressed with the crew identifications of badges and scarves which are an outward sign of this inward journey which was necessary for the neophyte to become a full member within society2.

D. The Sacred Nature of the Vigil

To increase the sacralization of the vigil, often Squires are advised to undertake their vigil out-of-doors, and at night. This is because if the Squire reflects on their deeds in their routine, predictable, safe, and comfortable surroundings, the answers may vary significantly than when done outside. Outside at night the Squire is exposed and vulnerable to the environment. This sentiment is also reflected by the founder's belief that it was through nature that the Rover Scouts could come to true knowledge of themselves, and what their promise means to them.

VI. A Right of Passage: The Rover Scout Vigil

In the specific case of the Rover Scout Vigil, van Gennep's territorial rite of passage is undertaken by the Squire. That is to say, upon completion of the probationary period, or Squireship, the Squire is removed from the community, separated from his original identity of Squire. S/he is taken into the woods, given the vigil questions and left there to undertake their vigil. The transitional period occurs while the Squire contemplates the vigil questions, his actions, and his responsibilities. The Squires at this time must also ask themselves if they are prepared to undertake the responsibilities of the Scout Promise and if they feel prepared to be Knights, be chivalrous, and perform service for others without a thought for themselves. After this has been completed, and any issues discussed with a "Sponsor," or trusted friend of the Squire, there are two possible rites of incorporation which can occur. The Squire may decide that he is not prepared to be a knight and will be reincorporated as a Squire. However, if the Squire feels prepared he is reincorporated as a potential knight, who, generally, will be knighted at dawn the following morning.

VII. Can the Rover Scout Vigil Change the Community Which Values It?

In terms of creating a sense of "Rover" identity in each Rover Scout, this is accomplished through the Squireship. During a Squireship the Squire will read Rovering to Success (Baden-Powell 1922) and undertake quests which perform service to the community. By the time a Squire has reached their vigil, they should, in theory, already recognize that the "Rover Scout Ideal" is incorporated within their identity, that is to say if after the Squireship they feel ready to become the ideal of a "knight." However, because the questions probe to the very core of the Squire's soul, asking them to reflect not only on the past good deeds, but also their past misdeeds, and how they treat other people, it is very easy to see why some people may feel unprepared for the responsibility of knighthood.

It should be noted, though, that because of the addition of new and diverse members and the leave-taking of other members, the community of Rover Scouts is constantly changing. However, the commonality between all of the knighted Rovers is their Squireship and vigil. The profoundness of the vigil questions are more likely, however, to change the individual than to change the community which values it. The creative possibilities of Turner's liminality in the Rover Scout vigil can produce a myriad of possible outcomes, such as maintaining the community, trying to live up to the community's ideals of knighthood and service, or, since this is a voluntary community, the decision that perhaps this is not the community for them to be in. As a result the Squire can try to achieve change within the society so that it is what they envision, or they can leave and pursue other interests.

VIII. Conclusion

Although many Canadians view Scouting as a secular organization in that they do not actively engage in religion, certainly throughout this youth movement rituals can be found everywhere, in every section. After becoming a legal adult in Canada, a youth can join the Rover Scouts, who ritualize entry into adulthood through the knighting ceremony in order for the neophyte to participate in a puberty rite, which Canadian secular society does not provide in any structured form. One aspect of this initiation rite is that of the vigil. Although liminality does arise during this ritual, with creative possibilities tend to affect the individual more than it changes the community which values the ritual though the use of symbolic ideals which, if the neophyte feels they cannot live up to, will not be initiated as a full member within that society.

Notes

- It should be noted that this book, although read by both men and women today, was originally intended for men. Therefore, although this section relates how a young man should choose a wife, the lessons are equally applicable to women in their choices of husbands.

- However, the ritual of the vigil within Rover Scouts is not only undertaken by Squires. K. R. "Smoke" Blacklock (1997), a Rover Scout Adviser from Northern Alberta has written "A Vigil for Two" in which questions are designed to aid in reflection on relationships between partners, such as marriage. There is also a "Rover Adviser's Vigil" (Scouts Canada 1994) which can be undertaken by new Advisers to be sure that they are prepared to undertake a promise of service to the Rover Scout Community. A vigil ritual can be written for anyone in any situation. Knightings are simply the most common situation in which to find them.

References

- Baden-Powell, Lord Robert.

- 1922. Rovering to Success. Sydney, Australia: Hogbin, Poole (Printers) Pty. Ltd. 1991 reprint.

- Blacklock, K. R.

- 1997. Through the Rapids. Edmonton.

- Kirchmeir, Peter.

- n.d. The Rover Dictionary. Edmonton.

- Morland, Liam.

- 2000. The Rover Vigil. http://ScoutDocs.ca/Documents/Rover_Vigil accessed on 2000-11-12.

- Scouts Canada.

- n.d.a. Rover Scouting. Ottawa: The General Council of the Boy Scouts Association — Canada.

- n.d.b. The Vigil of a Rover Scout. Ottawa: The General Council of the Boy Scouts Association — Canada.

- 1974. Rover Handbook. Ottawa: Boy Scouts of Canada, National Council.

- 1994. Crew Wood Badge Training Resources. Scouts Canada, Calgary Region.

- 1996. By-Law, Policies, and Procedures. Ottawa: Scouts Canada, National Council.

- 1997. Rover Program Handbook. Ottawa: Scouts Canada, National Council.

- n.d.b. The Vigil of a Rover Scout. Ottawa: The General Council of the Boy Scouts Association — Canada.

- Turner, Victor W.

- 1996. "Liminality and Communitas" in Readings in Ritual Studies, Ronald L. Grimes, ed., 511-519. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Van Gennep, Arnold.

- 1969 [1960]. The Rites of Passage. Trans. Monika B. Vizedom and Gabrielle L. Caffee. Chicago, The University of Chicago Press.

- 1996. "Territorial Passage and the Classification of Rites" in Readings in Ritual Studies, Ronald L. Grimes, ed., 529-535. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- World Organization of the Scout Movement (WOSM).

- 1992. Fundamental Principles. Geneva, Switzerland: World Scout Bureau.